Community Acquired Pneumonia

Community-acquired pneumonia refers to pneumonia that begins when the patient is outside the hospital, or within the first 48 hours of hospital admission. Patients previously categorized under "healthcare-associated pneumonia" are now considered to have community-acquired pneumonia due to evidence that the previous categorization fails to accurately identify patients harboring drug-resistant organisms.

Differential Dx

| Differential Diagnosis | Clues | Diagnostic Tests |

|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary Embolism | Wedge-shaped pulmonary infarcts may masquerade as pneumonia, unimpressive pulmonary infiltrates, right ventricular strain pattern on EKG/Echo, signs/symptoms of DVT (leg swelling, pain) | CT angiography |

| PJP (Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia) | HIV (if the diagnosis is known), chronic steroid use (>15 mg prednisone for >3 weeks), chemotherapy/immunosuppressive drugs, diffuse interstitial infiltrates | HIV serology, bronchoscopy with BAL sent for fungal stain & PCR |

| Endemic Fungal Pneumonia or Cryptococcus | Often more indolent than bacterial pneumonia, radiologic pattern often nodular, exposure to endemic locations, bird/bat droppings, soil exposure | Urine antigens (e.g., blastomycosis, cryptococcus), CT scan, bronchoscopy |

| Invasive Aspergillosis | Neutropenia (especially >10 days), high-dose steroid (e.g., pulse therapy for vasculitis) | CT scan, Beta-D-Glucan, galactomannan, bronchoscopy |

| Septic Pulmonary Emboli | Diffuse infiltrates which tend to cavitate, often bacteremic with Staphylococcus aureus, often seen in patients with intravenous drug use | CT scan, echocardiogram |

| DAH (Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage) | Hemoptysis (only 50% of patients), diffuse infiltrates, renal failure or active urinary sediment (hematuria), falling hemoglobin, may have previously diagnosed rheumatologic disease | Urinalysis, markedly elevated ESR & CRP, bronchoscopy, serologies (e.g., ANCA) |

| AEP (Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia) | Blood eosinophils over ~300/uL (unusual for severe pneumonia), younger adults with severe pneumonia often requiring intubation, sometimes inhalational exposure (esp. recent-onset smoking) | Bronchoscopy |

| COP (Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia) | Often more gradual onset than usual pneumonia, refractory to antibiotics | Tissue biopsy |

| Drug- or Radiation-Induced Pneumonitis | Exposure to drug implicated in causing pneumonitis (e.g., amiodarone, chemotherapeutics) | Diagnosis of exclusion |

| Flare of Interstitial Lung Disease | History of chronic pulmonary limitation, prior diagnosis of interstitial lung disease (often idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis) | CT scan, diagnosis of exclusion |

| Exacerbation of COPD | COPD exacerbation may clinically mimic pneumonia including hypoxemia, fever, and sputum production; isolated COPD exacerbation should lack infiltrates on chest imaging | Isolated COPD exacerbation: lack of infiltrates on chest imaging, relatively low procalcitonin level |

| Atelectasis (+/- non-pulmonary infection) | Chest X-ray isn't impressive, clinical illness severity is disproportionate to the X-ray abnormalities, lack of prominent pulmonary symptoms | CT chest |

| Aspiration Pneumonitis | History of aspiration or swallowing problems, repeated episodes of pneumonia with rapid recovery, infiltrates located in dependent lung segments | CXR, rapid clearance of CXR, procalciton |

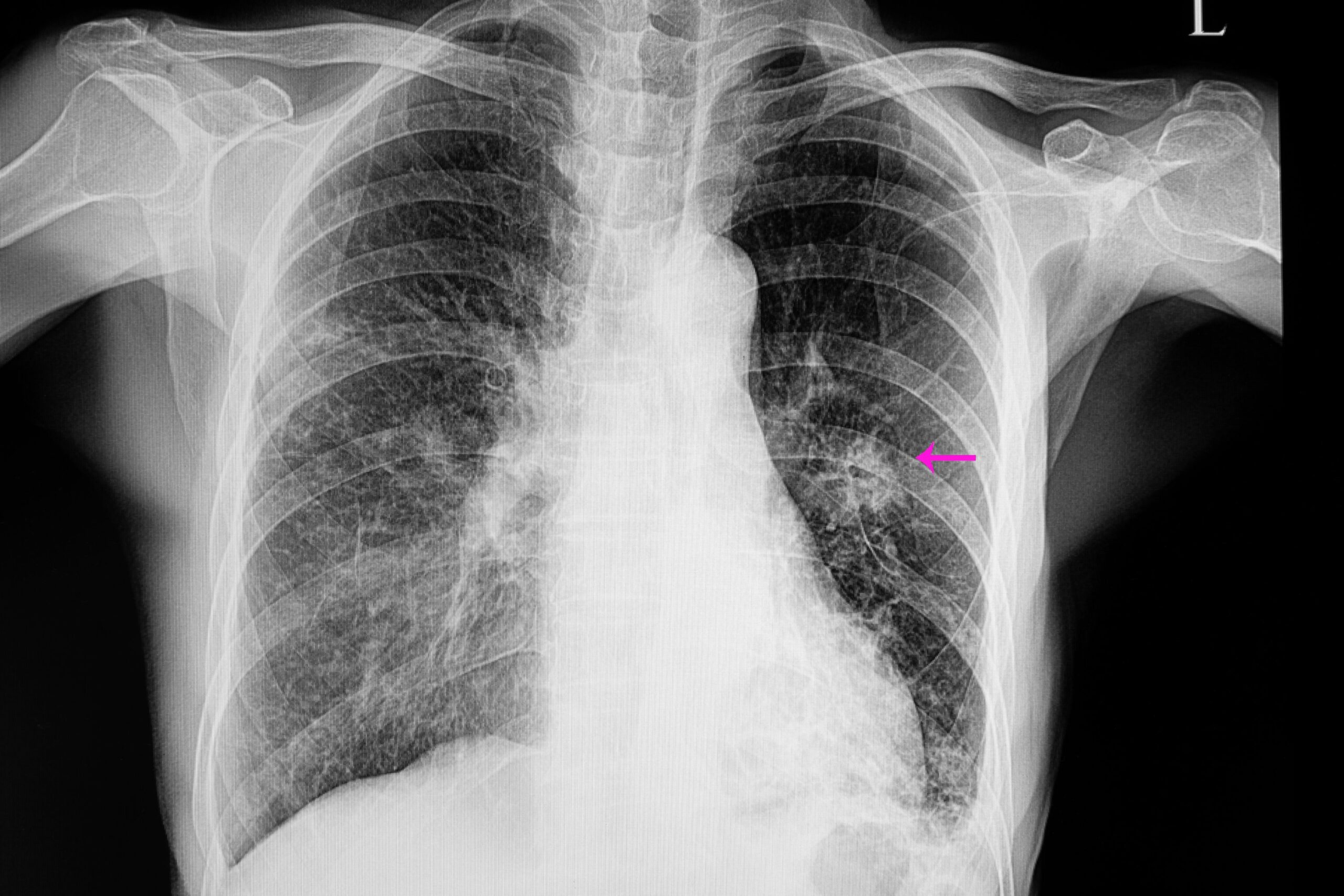

Diagnosing CAP

The diagnosis of CAP is generally based on three lines of evidence:

- imaging evidence of a chest infiltrate (like CXR, CT, ultrasound)

- systemic inflammation (symptoms: night sweats, rigors, fevers; signs: fever or hypothermia; labs: leukocytosis, left-shift, elevated C-reactive protein, elevated procalcitonin)

- localizing signs and symptoms (symptoms: dyspnea, cough, sputum production, pleuritic chest pain; signs: hypoxemia, tachypnea, abnormal lung ascultation).

There can be atypical presentations of CAP, particularly in elderly patients who may present with non-pulmonary complaints such as falling, delirium, or sepsis. When in doubt, it is recommended to get cultures and start antibiotics for pneumonia

CT scan can assist in the diagnosis of pneumonia, especially in patients with chronic lung disease and those who are chronically abnormal on chest X-ray. CT scan is more sensitive than chest X-ray and can detect pneumonia that may be missed in certain situations

Laboratory Testing

Following a diagnosis of pneumonia, various lab tests can be done such as:

- blood cultures (recommended for severe pneumonia)

- sputum for gram stain & culture for bacteria

- sputum for fungus culture & smear

- urine legionella antigen

- urine pneumococcal antigen

- nares PCR for MRSA

- nasopharyngeal PCR for COVID and other viruses

- procalcitonin and C-reactive protein (CRP)

- HIV screening test

Bronchoscopy

Bronchoscopy is rarely useful in the management of community-acquired pneumonia, but occasionally useful to exclude a non-infectious pneumonia mimic (like diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, eosinophilic pneumonia), or to exclude an unusual infection, primarily fungal pneumonia or pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.

Who Needs ICU?

The IDSA suggest ICU admission for severe pneumonia patients

- Major criteria: respiratory distress requiring mechanical ventilation and septic shock, with

- Minor criteria: respiratory rate >29 breaths/min, hypotension requiring volume resuscitation, PaO2/FiO2 <250, and other signs of physiological stress or impaired immune response

Common errors in pneumonia triage include basing decisions solely on the amount of oxygen the patient requires or relying on CURB65 and PORT scores, which are not specifically designed for ICU admission decisions.

CURB-65 Pneumonia Severity Score

Please check the boxes that apply:

Antibiotic Selection for CAP

| Antibiotic Selection | Tips |

|---|---|

| Atypical Coverage | Include atypical coverage in empiric antibiotic regimen for severe pneumonia |

| Legionella causes ~10-15% of severe pneumonia, not covered by broad beta-lactams | |

| Azithromycin: Solid track record in pneumonia - Well-tolerated and safe, no concern for QT interval prolongation | |

| Doxycycline: Covers organisms acquired from animal contact - Potential activity against MRSA | |

| Beta-Lactam Backbone | Ceftriaxone: Excellent choice for most patients - Controversy over dose (1 or 2 grams IV daily) and obese patients - Safe to use in most patients with penicillin allergy |

| Antipseudomonal beta-lactam (piperacillin-tazobactam or cefepime): - Generally safe for patients with penicillin allergy - Double coverage generally not necessary for pseudomonas, unless highly resistant to beta-lactams | |

| MRSA Coverage | Uncommon cause of community-acquired pneumonia, most patients do not need MRSA coverage - Tailored strategy for MRSA coverage based on risk factors |

| Linezolid: Arguably first-line therapy for MRSA pneumonia, superior lung penetration, no nephrotoxicity | |

| Vancomycin: Traditional option, increasing resistance over time, consider alternative if borderline sensitivity or MIC >2 mcg/mL | |

| Ceftaroline: Active against MRSA, may be superior to vancomycin, limited evidence available | |

| Anaerobic Coverage | Not needed for pneumonia, unless empyema or lung abscess is present |

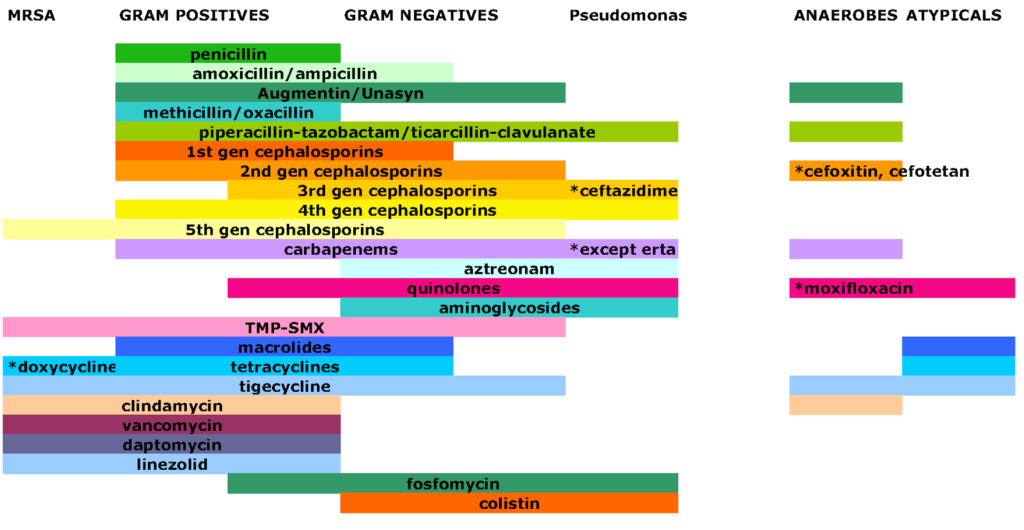

Common Antibiogram

Resuscitation

Large volume fluid resuscitation should generally be avoided as it can worsen hypoxemic respiratory failure. Vasopressors can be used to stabilize patients if needed. Fluid should only be used if there is organ hypoperfusion or refractory hypotension, and the patient's history and evaluation indicate true volume depletion.

- Respiratory Support

High-Flow Nasal Cannula (HFNC) may be beneficial for patients with significant work of breathing and/or tachypnea, as it can reduce work of breathing, provide oxygenation support, and promote secretion clearance. BiPAP is typically avoided due to its potential to cause retention of secretions. Endotracheal intubation is usually considered after trying HFNC, particularly for refractory hypoxemia or progressively worsening work of breathing.

- Steroids

Steroids may reduce the length of stay and risk of intubation in critically ill patients with Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP), although their impact on mortality is unclear. Contraindications include suspicion of fungal or tuberculosis pneumonia, immunocompromise, history of steroid-induced psychosis, and other specific cases.

- Pleural Effusion

Pleural effusion and empyema are common in severe pneumonia. These should be evaluated using bedside ultrasonography. Management is driven by ultrasonographic features, which determine whether to follow with daily ultrasonography, drain with thoracentesis, or place a pigtail catheter.

- Treatment Failure

Treatment failure may be indicated by lack of clinical improvement within ~3 days, persistent or rising procalcitonin or CRP over several days, or ongoing deterioration in oxygenation and infiltrates >24 hours after antibiotics.

Duration of Treatment

A time-based strategy suggests 5-7 days of treatment, with longer periods for certain conditions. A procalcitonin-based strategy suggests discontinuing antibiotics when procalcitonin levels fall below certain thresholds. Both strategies can be considered when determining the duration of treatment.

Antibiotic table for various infections

| Clinical Syndrome | Most likely pathogens | Reasonable initial empiric antibiotic agents |

|---|---|---|

| Community-acquired pneumonia inpatient therapy | Pneumococcus, H flu, M Catarrhalis, atypicals | Ceftriaxone plus azithromycin; respiratory quinolone (levofloxacin/moxifloxacin). If risk factors for resistant organisms (cefepime, piperacillin-tazobactam, meropenem, or imipenem-cilastin). Add vancomycin or linezolid if risk for MRSA. With severe COPD, consider using an antibiotic with pseudomonas coverage instead of ceftriaxone. |

| Hospital-acquired pneumonia (non-ventilator acquired) | MRSA, MSSA, pneumococcus, gram negatives including pseudomonas | Either piperacillin-tazobactam, cefepime, ceftazidime, levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, imipenem, meropenem. Add vancomycin or linezolid if IV antibiotics within 90 days, prevalence >20% or not known, high risk of mortality, or previous detection of MRSA. |

| Aspiration pneumonia in an alcoholic | Anaerobes, gram negatives, pneumococcus | Ampicillin/sulbactam; piperacillin/tazobactam; clindamycin plus ceftriaxone; metronidazole plus ceftriaxone. New guidelines only need anaerobic coverage if empyema or abscess. |

| IVDA with fever and pleuritic chest pain | Staph aureus including MRSA, enterococcus, gram negatives | Vancomycin |

| Nursing home patient with UTI + Foley | Gram negatives including pseudomonas, rarely enterococcus | Ceftazidime, cefepime, aminoglycosides, ciprofloxacin. Vancomycin if urine gram stain gram +s. |

| Diabetic foot ulcer (malodorous) | Anaerobes, gram negatives, gram positives including possible MRSA | Piperacillin/tazobactam plus vancomycin for MRSA |

| Intravenous catheter | MRSA, MSSA, occasionally gram negatives including pseudomonas | Vancomycin but add pseudomonas coverage if acutely ill |

| Cellulitis requiring hospitalization | Gram positives including streptococcus and staph aureus including MRSA | If purulent cellulitis, need to cover MRSA. If non-purulent, then likely streptococcus. If purulent, usually vancomycin for MRSA, but if non-purulent, cefazolin for strep and MSSA. |